Vol. 1 no. 4

|

My father drove me down to Boston, and Berklee, the old school on Newbury St. I remember going into Bob Share's office, sitting in there and talking about the high tuition. It was a thousand dollars, which in those days was a lot of money. I remember him saying to my father, "If he practices and does well, you never can tell what he's going to do." I really wanted to study and do well at Berklee because they had everything I needed; the arranging courses, the ensembles, the playing of jazz in the classes. It was the heyday of Berklee; Lin Biviano was there, John Abercrombie, Gene Perla, Sadao Watanabe. Later on Miroslav Vitous arrived, my brother John came from Potsdam, and my brother Joe came directly from high school.

I was there from 1964-67. Every summer I returned home to work in the

canning factory or drive trucks. I had been studying seriously with Joe

Viola, and during my last summer break I felt confident enough to chance

picking up a gig in the Boston area. A few days into the break, I got a

gig through the student bulletin board postings. It was a jobbing gig in

Old Orchard Beach, Maine, then a popular area for French Canadians. The

trumpet player was Keith Green, who later supervised the Ringling Bros.

circus bands. The leader was a piano player named Richard Frank He had an

Air France cardboard cutout of the Eiffel Tower (it stood four or five feet

tall). Richard would play the intro to the Marseillaise, sustaining

the last chord while he whipped out the cutout and placed it firmly on the

piano like Liberace's candelabra, then Keith and I would shout, "C'est

Magnifique," and we would play it.

I was there from 1964-67. Every summer I returned home to work in the

canning factory or drive trucks. I had been studying seriously with Joe

Viola, and during my last summer break I felt confident enough to chance

picking up a gig in the Boston area. A few days into the break, I got a

gig through the student bulletin board postings. It was a jobbing gig in

Old Orchard Beach, Maine, then a popular area for French Canadians. The

trumpet player was Keith Green, who later supervised the Ringling Bros.

circus bands. The leader was a piano player named Richard Frank He had an

Air France cardboard cutout of the Eiffel Tower (it stood four or five feet

tall). Richard would play the intro to the Marseillaise, sustaining

the last chord while he whipped out the cutout and placed it firmly on the

piano like Liberace's candelabra, then Keith and I would shout, "C'est

Magnifique," and we would play it.

I had played on this gig for about a month and a halfwhen my brother Joe called and said "You know there's a jazz gig opening up at Avelock." Joe was working in Tanglewood with Chuck Israels and Hod O'Brien, and the Avelock was a club nearby. Randy Weston had just left the club, and there was an opening for a student band. I gave my notice and finished the summer playing jazz every night. It was the first time I'd ever played a six night a week jazz gig.

The band shared a house together with Gene Gammage, a seasoned professional who had played with Oscar Peterson and recorded with Jack Sheldon. He had studied magic with John Scarney. Through Gene, I developed a passion for magic which I later studied and practiced during my band bus days. Later, Gene would introduce me to guys around New York City when I came to town. He disappeared suddenly in the mid-seventies. If you ever hear what became of this great drummer, I'd certainly like to know.

I went back to Berklee in September 1967, and the alto player Jimmy Mosher

recruited Jerry Bergonzi and me to play in his Berklee big band. One night

in late October he told me, "You've been in school too long; you should

be out on the road." He had just left Buddy Rich's band to play locally

and teach. "As a matter of fact, " he said, "I know that

there's a job opening up in Buddy's band." This was a Friday night

and we were drinking after a rehearsal. He said, "I'll make the call,

and you can have the gig on Monday." I thought, 'Yeah, right.' So Monday

I saw him and said, "OK where's the gig with Buddy?" and he said,

"You leave Thursday. Finish up your stuff, get out of your classes

and get ready."  I also had to get out of the Berklee recording band, which

pissed a few people off, but I figured, this was it, I gotta do it. I took

the train to Mount Morris, packed a few things, and that Thursday I flew

to New York.

I also had to get out of the Berklee recording band, which

pissed a few people off, but I figured, this was it, I gotta do it. I took

the train to Mount Morris, packed a few things, and that Thursday I flew

to New York.

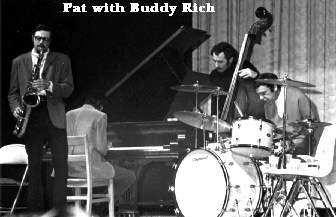

I knew one guy in the band. I had played with Ernie Watts at Berklee in Charlie Mariano's sax section. I was a little intimidated, especially when I got a copy of our tour schedule. The first job was in Minneapolis-St.Paul. It was a birthday party for Hubert Humphrey, and there was a huge cavalcade of acts, hosted by Bob Hope and Milton Berle, and the performers were Nancy Sinatra, The Fifth Dimension, Morgana King, and finished with Frank Sinatra! I had time to rehearse the fourth tenor book but Jay Corre, the tenor soloist, missed his plane because of the weather. When I arrived I was informed that I had to play the first tenor book. I just had to get through it the best I could. Two months later we went to L.A.; sometimes we would work there for a month in order to go on a major tour. We went all through the Orient and stayed there through Christmas.

AW: All those stories you hear about him yelling, are they true?

PL: Buddy could get very verbal, but I've talked to guys about that, guys that could really play. Every one of them respected Buddy. Here was a guy who was in his fifties, who played hard every night. If you get a young guy in his twenties who is messing up, who is high or drunk, then it doesn't mix. Buddy figured if you are that young, you should at least be able to play up to him. He would get on people. Maybe it wasn't always justified, but he would make it clear when he was unhappy. His personality was the same as a lot of leaders from that era; Tommy Dorsey, Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis, they all were taskmasters. Now everybody is kind of vanilla, you know, loose and sometimes the music reflects that. Listen to Miles' band, they have freedom to play, but there is discipline, and it was structured by Miles. Buddy gave us freedom to play, but you had to PLAY. It was a great job for me. I loved playing with him.

AW: Did Buddy ever talk about some of the guys he'd played with?

PL: Sure. He would tell us stories about Bird, Lester Young, Tommy

Dorsey. He loved Papa Joe and Gene Krupa.

AW: When you first started playing with him, what was it like?

PL: He was cool, he let me play. I had a couple of solos, but he wanted it perfect, and we'd have sectionals every day. There was kind of a rivalry between sections, everybody was trying to get their parts perfectly. They were hard charts. I wasn't just being a local player any more; now all of a sudden I was backing Ella Fitzgerald and Nancy Wilson, and I was playing jazz festivals. Miles would come in to see the band, we were on the (Ed) Sullivan and (Johnny) Carson shows. Every jazz drummer in the world would come in to see Buddy. We got to meet them and hang out.

Buddy introduced me to Sonny Rollins; I was standing on the stoop of Basin Street West in San Francisco, when Sonny came by on his way to the Jazz Workshop. Buddy introduced us, and I asked Sonny for lessons. He was in a rush, but kindly offered to come back on his break to give me his phone number and make arrangements. Can you believe that? I quickly said no, that I would go to his gig down the street. I talked to Sonny many times on the phone, and he was always generous with his time and advice, but we could never hook up time-wise for a lesson. He did come in to hear me with Elvin in later years; he recognized me, and asked how I was doing just before we went on stage. That's pressure; playing with Elvin, with Sonny standing in the wings listening to your solos.

Buddy put my name out there. I would never have had that kind of work had I stayed in Boston. I was intimidated at first, but the band played every night so that helped me keep it together and hone my playing. I met so many guys who influenced my playing, like Joe Romano and Don Menza. People still come up to me in clubs to talk to me about concerts or recordings I did with Buddy. Even if they never heard the band live, they still heard me on the records. The Buddy thing got me recorded and recognized. Everybody came in to see us. Philly Joe and Art Blakey would sit in. Philly Joe would be his valet when he wasn't working; he'd set up the drums and get them moved. He also played sax, and we would talk about mouthpieces, he had some of Trane's old mouthpieces in Philly.

Through Buddy, I got to meet Elvin. He and his wife came to Ronnie Scott's in London; Dave Liebman was leaving the band, and they asked me if I would be interested in joining. It was another year before I got the call. By then Buddy had broken up the big band to open up his New York night club, and I had moved to Canada. I was ready.