Vol. 1 no. 4

AW: Why Canada?

PL: My first wife and I were expecting our first child in 1974. We wanted to raise our family near her mother in Lindsay and my parents in Rochester. I had a lot of friends from Vancouver; Buddy would play Issy's in Vancouver, and I met Bernie Senensky, Don Thompson, Terry Clarke, Dave McMurdo, and Dave Field. We would play together at a place called the Espresso during the late sixties. In the seventies they all moved to Toronto, and would play at George's. Every time I came through Toronto, these guys would be playing, and I thought, this is a great place. There were so many great rhythm sections, but there weren't that many saxophone players. Alvin Paul was on the scene, and Ronnie Park, Eugene Amaro, and Rick Wilkins. I thought, this would be a great place to live. Plus it was close to Rochester.

Marty Morrell came here at the same time I did. The first thing I did was play at the Belvedere Jazz Festival. Marty was on it. I subbed for a player in Louie Bellson's big band. Don Menza, Herbie Steward, Blue Mitchell, and Frank Rosolino were in the band. We played Toronto, then Vancouver, then toured Canada with the jazz festivals. After that, I thought, well that's good, I can work and play jazz in Canada.

There was a union rule that for six months a new member could not take a steady gig. I had a baby on the way, so I would drive down to Rochester to work with an accordion player on jobbing gigs. Then a guy named Hugh Claremont hired me for weekend gigs in Orillia, north of Toronto. The union didn't monitor them so I was able to work without leaving the country. But I scuffled for two years. The musicians who had been in Toronto for years, of course, were first call. It was hard to break in.

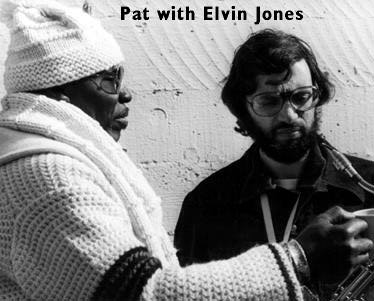

When Elvin called me in 1976 to replace Junior Cook I had a second child on the way, and I decided to go on the road again. Then his bass player Gene Perla offered me my first record date under my name. I thought this was great, I'm getting my first record date and my first call to go with Elvin. Elvin just called and said, "We're going to rehearse. Come down on Saturday, and we open on Tuesday night at the Vanguard."

So I flew down Friday night and checked into a hotel.

I called him up Saturday and he said, "Well, I can't rehearse today,

something's up, plaster is coming down in the house." Then I called

him on Sunday and he goes, "No, I'm not going to be able to rehearse

today. Maybe tomorrow." I called on Monday and he said, "No, I

can't rehearse. You can play, just show up at the Vanguard." So I showed

up at the Vanguard; there was no music, but luckily I had some tapes I had

made. I knew some Coltrane tunes. None of the stuff was written out.

So I flew down Friday night and checked into a hotel.

I called him up Saturday and he said, "Well, I can't rehearse today,

something's up, plaster is coming down in the house." Then I called

him on Sunday and he goes, "No, I'm not going to be able to rehearse

today. Maybe tomorrow." I called on Monday and he said, "No, I

can't rehearse. You can play, just show up at the Vanguard." So I showed

up at the Vanguard; there was no music, but luckily I had some tapes I had

made. I knew some Coltrane tunes. None of the stuff was written out.

Thankfully, Frank Foster was on the gig; Elvin had hired him to cover me. I got down there and Frank taught me the tunes in the kitchen before we went on each set. Foster was great to work with; we always had fun together. All the older players I worked with were great people.

AW: When you worked with McCoy and Elvin, what was that like?

PL: We'd go on these special tours; McCoy, Elvin, Richard Davis and me. We did some concerts in France and some TV shows. We worked the Lighthouse in L.A. I got to meet Harold Land and Teddy Edwards and Horace Silver. With Elvin's band you'd meet a lot of great players and get to play with them as well. Freddie Hubbard used to sit in, Chick Corea, Tommy Flanagan, people like that.

AW: And when Tommy Flanagan would come by and play, would the tunes be different?

PL: Yeah, we would play Blues and things like that. Jones, although you might think of him as an extremely modern drummer, he would turn to you some nights and say, "Just You, Just Me," or some other old tune. Some of the younger guys in the band wouldn't have a clue. He allowed me to bring a lot of material into the band. Jones loved ballads and I tried to bring in older obscure Tadd Dameron ballads that nobody played. He let me write originals, and never gave any kind of critical direction, except to tell me I didn't play long enough. When I first joined, I was still used to the big band capsulization, you know, shotgun tenor. So he said, "Take your time, you got lots of time." It was great.

AW: Did you ever feel any kind of vibe because you were the only white guy?

PL: No. There were times when you would feel it from people that were not in the band. I remember when we got to Germany one time, and it was Elvin, Ryo Kawasaki, David Williams and myself. The promoter was kind of shocked to see Ryo and myself, because he said in a very thick accent, "But I thought you was an all coloured band..." and Elvin said, "Yeah, we are. We're all colours!"

That's the funny thing about Jones; he never really saw a colour line. He was one of these guys who just doesn't notice. He didn't like all the boundaries. He just judges a guy on how he plays. He used to get calls from record producers saying, "We have to have a black tenor player," and the press in Sweden would refer to me as, "The white tenor player." I try to not pay attention to that stuff. I know that there are black players who are proud of jazz being a black music, and should be, and they may tend to hire black players, and that's fine. I like to hire and work with the best player for each project. When I was on Buddy's band, he never allowed anyone to make the band go through the back door. They tried that at the Royal York and he said, "The band doesn't play." At a place called the Top Hat in Windsor, they wanted us to come in through the kitchen. Buddy said, "Forget it, I'm out of here." He cancelled a tour in South Africa because they found out we had a black bass player and they asked him to make a personnel change.

I think the guys that came up during the period of the forties and fifties, even though there were problems, they were a little more tolerant toward each other's goals. The music is too hard to play to allow any outside crap happening. It's challenging enough to keep your chops up, to tap your inner resources.