Vol. 1 no. 4

AW: So as you were playing in Elvin's band, you were also working in Toronto?

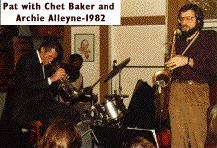

PL: Yes. Once I started working with Elvin's band, I started

getting calls here. Paul Grosney was really helpful; he got me into Bourbon

Street, working with people like Chet Baker and Lew Soloff. I started

getting work at George's, and other clubs with a quartet. Dave Kaplan

was an agent who was responsible for keeping a lot of the jazz scene going

in Toronto in the seventies and eighties.And I was able to record my band

with CBC Records and and Justin Time. Other musicians called me to work

on their records too.

PL: Yes. Once I started working with Elvin's band, I started

getting calls here. Paul Grosney was really helpful; he got me into Bourbon

Street, working with people like Chet Baker and Lew Soloff. I started

getting work at George's, and other clubs with a quartet. Dave Kaplan

was an agent who was responsible for keeping a lot of the jazz scene going

in Toronto in the seventies and eighties.And I was able to record my band

with CBC Records and and Justin Time. Other musicians called me to work

on their records too.

After Elvin, Don Thompson and Neil Swainson, my brother Joe and I put together a band called JMOG. We wanted to write original music and work off each other's energy. It's difficult to manage because Joe lives in L.A., so we have to fax each other music, and have one rehearsal before a gig. We've been able to work one or two weeks a year and record one CD, but all of us are busy with separate projects.

It's a good town, Toronto; I've always said that there are some great players in this town. You can't work six nights a week in any other place in this day and age. I have friends in L.A.; if they get two nights a week they consider themselves lucky.

Pat with Red Rodney and Don Thompson at East 85th

AW: What kind of stuff did you work on as you were developing?

PL: I was a practice freak. Even when I was working in Old Orchard Beach, I would find places. I remember they wouldn't let me play in the hotel, and I couldn't play on the beach. I went to the mayor of the town and I told him I had to practice and asked if there was a place I could play. There was an old town hall, and he said, "Take the attic and play anytime you want." On the road I'd learn how to find these practice rooms; I'd get into a hotel, I'd check to find out where the ballroom was, and I'd go from there. I remember Art Pepper (I was on the road for a year with Art); he used to tell me he would go and watch Coltrane practice. He said Trane would come to town, and Art would find out where he was staying, and he'd call him up and say, "Can I just come down and watch you play?" He said Coltrane would always go down into the boiler room and practice, in the summer, a towel around his neck, no shirt, down in the steam room. Art would just get a chair and he'd sit there all day and watch him practice. You'd hear stories like this and you'd think, if this is what the guys who you want to be like are doing, you gotta jump on it pretty fast. So I practiced a lot.

AW: I remember when I first met you, and we played at the Jazz Bar in Montreal, you were telling me about working on arpeggios. I remember being very impressed by the way you thought about playing chords on the saxophone.

PL: Oh yeah, I remember that; that's when I was trying to get away from scales. I did that because I had started researching Trane solos. I was looking at it from a linear approach, and I could see that, where he was doing the "sheets of sound" thing, around 58 or 59, it was like looking at a graph. And then around 62 or 63, it's an arpeggio. What he did was basically to work backwards; he went back to where Coleman Hawkins and those guys were. So I figured I had to go back and see what was going on here. Because that's the way I started to play. I played first from arpeggios and then on to the scale thing. So when I went back to arpeggios again, I found out that the chords allowed me to create more melody in the bar. Now it' s probably a cross-section of both, and I' m working more with rhythm, looking for short rhythmic things that I like to do.

AW: How do you see Coltrane's "outside" playing?

PL: He's playing tonally; he may play unusual tonalities in different spots, but he's tonally based. A great example is his solo on Shifting Down or Double Clutching. He does a little technique in there that I see come up all the time. It's funny, because I was recently analyzing a Jerry Bergonzi solo, and it's right there, the same thing. He'll play a blues, say in G on the tenor, so he'll play a D minor arpeggio, an F# minor arpeggio, then a Bb minor arpeggio back to a D minor. You can see it; he'll either do it as a chord or scale, but he'll use those three roots, sequential major thirds. Now you go to the modal period, and you can see the stuff that's "out" and the multiphonics, and you can see where he refers to Giant Steps, stretched out here and condensed there, and then you'll see harmonic shifts over pedal areas where he has kind of divided the octave into minor or major thirds. Then there are areas where he is just searching, but most of it is tonal. It doesn't always sound like it, because he has such tremendous technique that he can move so fast so that the ear doesn't catch a lot of it. When you see it transcribed, you can visually see it.

AW: And you must have talked to McCoy about this as well.

PL: I asked McCoy about a lot of harmony stuff; he doesn't do the division like Trane did. It's more of an ear thing with him, from the piano perspective. It's a little different way of shifting. We talked more about Giant Steps and Naima, in that period. I asked him about pentatonics; he would play stuff for me, but by that time I was kind of set on my own course. He told me that the only instructions that Trane ever gave him were to keep the harmony moving, don't be static.

AW: Did you get the impression that those guys didn't talk about the music?

PL: Yes. I don't think they did very much. From what Elvin said, first of all they hardly ever had rehearsals. He said you could tell when Trane was working on stuff though. I saw him (Coltrane) in Rochester, and I remember very vividly, he was playing something, and he kept repeating it. I thought, what is he doing, why is he repeating it so much? He kept getting more and more upset when he couldn't get this passage. And so he just ended one of the sets, took the tune out, and into the closet he went, trying to work this thing out.

When I was in Boston, we used to go to the Jazz Workshop; they would let us in for a buck. A friend of mine was a waiter there, and he used to sneak us in early, before the band would get there, and Trane would be there two hours early, practicing in the room by the toilet. We'd go there early, order a coke, and listen to him practice. Three or four of us sitting at the table saying, "Oh, what's that?" "What's he doing there?" We didn't know; everything was moving so fast.